|

CLAUDIA GARY _________________

SONG

AS

CONVERSATION ___________________________________

To me, setting a poem to music is a multi-level conversation: first between the composer and the poem, then between vocal and instrumental lines, and finally between performers and audience. I strive for a strong melody, and I want the music to enhance the words, just as a poem’s form can enhance its own content. This conversational aspect has led me to enjoy setting poems by others more than setting my own poems to music. Both poetry and music unfold in time, but in a song, the two elements do not necessarily unfold at the same pace or in the same manner. Since each of the two art forms has various ways of dividing time and space, the conversation between vocal and instrumental lines takes on many dimensions. Some of these—melodic variations, counterpoint, shifts between major and minor, etc.—may or may not relate to the words of the poem. To divide time, for example, we have the number and type of feet in a line of poetry, or the number of beats and durations of notes in a measure of music. In music, there are also various ways to divide tonal space—an octave, for example, can be divided into a third and a sixth, a fourth and a fifth, or a series of single steps. What carries me through the development of a song is a focus on the conversation. But for this to begin at all, I need to connect emotionally with the poem. Often this starts with a phrase that catches my ear and imagination. I look for strong, evocative images in the words, and avoid things that may be confusing to a listener, such as complex syntax, misleading homonyms, or too much abstract language. I might look at a poem’s first line, say it aloud, and see if I can imagine a musical line emerging from it. In either poetry or music, what often inspires me to write down a particular phrase to pursue later is an ambiguity or richness, together with a sense that there’s something more in it that may be worth exploring. The spirit in which I must do all of this, of course, is the spirit of play. If I feel that the first line of the poem can give rise to a musical line that’s intriguing and memorable, I play with that line and see what it needs in order for the words to be singable, based on what I’ve learned from Bel Canto training. If that works, then I go on to the next line of the poem, and so on. (Sometimes it’s OK to excerpt, cut, or shorten lines of a poem—if the poet agrees.) Music definitely appeals to the emotions, but I think it needs to appeal to the intellect as well. Melodic and rhythmic variations, harmony, major/minor shifts, differences in phrasing, and counterpoint are among the many types of play that can appeal to both.

Emotion and beauty in music: Where do they come from? As an example of emotion that’s overlaid onto music, rather than earned within, we all tend to be attached to songs we heard (and may have danced to) during adolescence. Such attachment may have little or nothing to do with the musical aspects of those songs—or it may be a combination—but it can last a lifetime. I’m not saying this is a bad thing! But it is different from emotion that is earned entirely within the music. Then there’s beauty, which became a controversial notion after World War II. The poet Richard Moore, who taught English at the New England Conservatory of Music for several decades, wrote in his essay “The Uses of Poetry for Musicians”: “How can one make a beautiful reflection of an ugly world, which is yet true to that world? An account of the ways in which this paradox has been resolved becomes an account of the triumphs of artists.” Frederick Turner explores the concept of beauty quite wonderfully in his book of essays Beauty, the Value of Values, among other places. I agree with both, but since it’s not easy to define or agree upon what makes a piece of music beautiful, I will speak only for myself. For me, the emotion of creative discovery is one of the greatest forms of beauty, and can inspire tears of joy. A discovery for the composer can be a discovery for the listener. (“No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader,” as Robert Frost said of poetry, can also apply here.) A moment

of creative discovery may, for example, be based on a revelation of

surprising depth in something that had appeared simple, or rediscovery

of a melody that seemed to be lost. This happens in some of Schubert’s

songs (such as his settings of three Petrarch sonnets, D. 628, 629, and

630); and those of Beethoven (such as “An die Ferne Geliebte,”

Op. 98; or his three settings of a single poem,“Sehnsucht,” WoO

134). Those are just a few examples of music that can seem to heighten

life’s meaning. It has also struck me when I’ve had the opportunity to

sing some of those songs, or to sing in the midst of a choir that was

performing Mozart’s Requiem or Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony,

that being one voice in a choir, or one part of a duet, and learning to

hear, simultaneously, the individual voice and the complete piece, is an

amazing experience. It can help develop the ear, the mind,

and even one’s identity. In some ways it may epitomize life. I am comfortable with dissonance provided it is eventually resolved and not used just for its own sake. It can, if resolved, provide an engine for driving a composition forward. But I think unresolved dissonance and atonality, much like free verse, can limit rather than open creative possibilities—and here’s why. Tonality in Western music, like form in poetry, offers a pattern of expectations in which to develop meaning. It also offers something more. Just as a given poetic meter or form gives context to metrical or other variations, and a song’s regular rhythm gives meaning to syncopation, so also does a clear tonal “home base” give meaning to tonal exploration. With such a home base, one can wander away—that is, modulate to other keys—and then return. Without such a home base, that sort of journey can have no homecoming. In this sense, tonal composition has a certain quasi-narrative potential that I don’t find in atonal music.

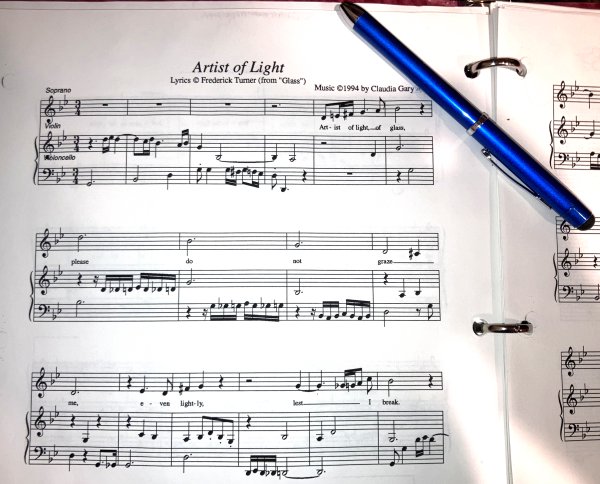

Melody, memory, and method This is much more easily said than done, but was certainly a goal of mine in “Artist of Light” and “Song of Creation,” which are the last two songs of a cycle I composed in the early 1990s, to be performed by a trio: soprano, violin or clarinet, and cello. The cycle is titled “Compos Mentis” — meaning “of sound mind,” in contrast to the legal term “non compos mentis.” The lyrics are poems by Frederick Turner, Dana Gioia, and Heinrich Heine (as translated by Turner). A sound file from a live 1994 performance of the two songs is attached to this article. There is no comparable recording of the entire cycle, although rougher recordings can be found on YouTube by searching for “Compos Mentis” and my name (without quotes). If you do listen to the entire cycle, please consider closing your eyes after the opening credits, as it is accompanied by a needless slide show. I should mention that the attached recording of “Artist of Light” and “Song of Creation” was originally made using audiotape; it was later converted to DVD, and then to an MP3 file. Philip Quinlan — another poet-composer who formerly edited the now-archived Angle Poetry Journal, and who interviewed me for Angle in 2014 — worked wonders to enhance the sound file and cancel some noise. The multiple media conversions and the age of the recording did result in some slight distortions of pitch and tone, but I hope listeners can “hear through” those flaws. The performance itself was part of a reading and concert organized by Frederick Feirstein, which took place at a Barnes & Noble bookstore in NYC, somewhere around 5th Avenue and 20th Street, in a building that may now contain a health club. The musicians with whom I was very fortunate to perform that evening are clarinettist Steve Hartmann and cellist Eugene Moye. While their training and mine, plus one rehearsal, helped allow intellect to lead the way, it was a very emotional experience! “Artist of Light” is my setting of a brief excerpt from Frederick Turner’s longer poem, “Glass.” The excerpt is as follows:

...Artist of light, In setting these lines, I began as always with an intuitive melodic idea and then developed it using, among other things, canonical exercises along the lines of what Bach taught to his students. Once I had a melody that seemed worth exploring, I focused on creating a conversation between the singer and the instruments, as well as between the clarinet and cello. As this interplay proceeds, the vocal line is echoed and varied by the instrumental lines, and the lines take turns being in the foreground. The development involves syncopation, variations of motif, as well as counterpoint between fast and slow versions of the melody. It speeds up and slows down to convey shifts between intense emotion and calm reflection. There are also tonal shifts, as well as returns to “home base.” At the end of “Artist of Light,” there is a modulation that does not shift back. I generally would never do this if a song stood alone, but I included it as a transition to “Song of Creation,” which is the last of five songs in the complete cycle. The poem “Song of Creation” is Frederick Turner’s translation of Heinrich Heine’s “Schöpfungsliede.” This poem—which Heine meant to be spoken in the voice of God—clearly states the theme that inspired me to compose the entire song cycle, which is that creativity can help us to become, and stay, sane: Why,

truly, I created all

Sickness indeed is the last ground Since “Song of Creation” is a setting of a rhymed, metrical eight-line poem, it would seem logical to make the song simpler in terms of structure. But in fact—just as poetic forms, meter, and rhyme can give us unexpected freedom in composing poems—the regularity of this poem’s form allowed me more freedom to vary the music. This song may have a greater degree of rhythmic predictability than “Artist of Light,” but it, too, takes tonal excursions, including one near the midpoint and another near the end. In the latter, it ventures into new territory just when everything seems to have settled. The eventual ending may seem overly definitive for a brief song, but this of course is also the conclusion of the song cycle. If you listen to the entire cycle on YouTube, you’ll find that it includes settings of two poems by Dana Gioia (one an excerpt). You’ll also find that the melody of the cycle’s last song is related to that of the first one, which is based on Frederick Turner’s poem “Spring Evening.” (Links to “Artist of Light” and “Song of Creation,” as well as two more recent songs of mine (very short ones), are provided below along with notes and references.) Classical music is not, or does not need to be, a lost art of the past. In this essay, although it was not possible to fully explain compositional method, I have attempted to demystify it. Just as “new formalist” poets (as well as those who never discarded meter and rhyme) have often created a counterpoint between old poetic forms and today’s language, I do think it’s still possible for classical forms to provide a framework for memorable and vibrant music. I am hoping to offer more such music in the future. NOTES & LINKS The author presented a shorter version of this essay, along with the musical examples, on Oct. 21, 2022, at the 25th annual conference of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers. It served as part of Diana Senechal's seminar on Setting Poetry to Music, some of which can be found at https://straightlabyrinth.info/conference.html. Artist of Light / Song of Creation (poems (c) by Frederick Turner and Heinrich Heine; Heine translation (c) by Frederick Turner; music (c) by Claudia Gary) Scenario (poem (c) 2007 by Micheal O’Siadhail; music (c) by Claudia Gary) If Only (poem and music (c) by Claudia Gary) Richard Moore: The Uses of Poetry for Musicians. Frederick Turner: Beauty, the Value of Values (University Press of Virginia, 1991). music (c) Claudia Gary; lyrics (c) their respective authors

|

Writing

poems, composing music, and listening to classical music have all

fascinated me since childhood. But what I’ve composed since studying

classical composition and Bel Canto singing, both during my 20s, is very

different from the songs I wrote for voice and guitar at 14. Back

in my teens, it was pure inspiration and intuition. After learning some

of the methods that composers such as Bach and Mozart used and taught to

their students, practicing with those tools, and listening to more and

more classical music, I found myself writing “art songs" in the Western

musical tradition.

Writing

poems, composing music, and listening to classical music have all

fascinated me since childhood. But what I’ve composed since studying

classical composition and Bel Canto singing, both during my 20s, is very

different from the songs I wrote for voice and guitar at 14. Back

in my teens, it was pure inspiration and intuition. After learning some

of the methods that composers such as Bach and Mozart used and taught to

their students, practicing with those tools, and listening to more and

more classical music, I found myself writing “art songs" in the Western

musical tradition.