EP&M Online: Response, Salemi to Darling,

II

The L-Word and Other Matters:

A Second Reply to Robert Darling

by

Dr. Joseph S. Salemi

Department of Classics, Hunter College, CUNY

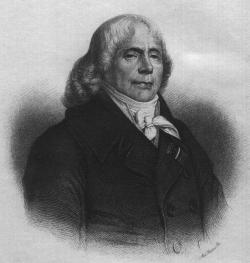

Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand

Prince de Benévént

One of the rhetorical successes of leftists in

the 1950s was the invention of the phrase "Red-baiting." It

was used as a convenient whip whenever anyone brought up the question

of Communist influence in American society. If you asked about

someone's political loyalties, or raised legitimate security concerns,

a platoon of enragés from the editorial staff of The

Nation to the executive board of the ACLU screamed "Red-baiter!"

at you. Here in New York, the late Bella Abzug used it against

anyone who brought up her Stalinist past.

Well, the phrase "Red-baiting" has died with

the Reds, but liberals still employ a variant of it in debate.

They now complain about "the L-word" or "the liberal card."

The procedure is as follows: If anyone mentions the fact that you

are a liberal, don't confirm or deny the charge. Just huff and puff

indignantly about "the L-word," and hope that everyone will forget

that you haven't admitted anything.

Since Robert Darling makes such a big issue

of my references to liberals and liberalism, it's time to clear the

matter up. Is Darling a liberal or not? And if he is, why in

his lengthy essay did he not acknowledge the fact? Is he ashamed

of his politics? It would seem that, just as those in the 1950s who

screamed "Red-baiter!" would never say whether or not they were Reds, so

also people who fulminate against "the L-word" never admit whether

or not they are liberals. So how about it, Bob? Enlighten

us, just for the record. After all, you're an "Enlightenment

Puritan."

The issue is not a trivial one, for the only

serious charge Darling brings against me in his essay is that I made

an "ad-hominem" attack on him by suggesting that he is a liberal.

Well, let's look at this logically. If Darling is a liberal,

then why should he consider the suggestion damaging? Perhaps Darling

does not know the precise meaning of the phrase ad hominem.

It means "to the person," and refers to arguments which are directed

not to the issue at hand, but against the individual defects of one's

opponent. Does Darling believe that liberalism is a defect?

Consider the forensic possibilities.

Darling could have replied "Yes, I'm a liberal and proud of it!"

Or he could have said "I'm a liberal in this or that respect, while

I'm not a liberal in some other respect." Darling does neither.

He just talks derisively about "the L-word." That's merely a way

to strum the chords of centrist orthodoxy.

In my last essay here I stated my political

views forthrightly, making no bones about the fact that I'm fiercely

proud of my rightist views. But Darling apparently thinks that

just being called a liberal is to suffer a grievous ad hominem

attack. Why should that be, if he honestly believes in his opinions?

Is it that he's trying to straddle the fence on this issue? There's

some real evidence for this, as I'll show a little further down.

Moreover, while we are on the subject of personal

attacks, Darling has a few things to answer for. He refers

to me as a "fundamentalist," a term of abuse long flung by lazy thinkers

at anyone who has a more coherent worldview than they do. I

wouldn't mind that, but Darling knows quite well that in the superheated

atmosphere of America today, the term "fundamentalist" now also conjures

up images of murderous Islamic terrorists who kill helpless civilians.

This is like screaming Collaborateur! at a Frenchman in 1946.

It's a very dangerous and threatening charge to make in a post-9/l1 context.

Was this just accidental on his part, or is Darling trying to connect me

with Al Qaeda? If so, let him spit it out plainly.

In addition, Darling's bush-league prejudices

are showing when he refers to my mention of my Roman Catholicism

as a "confession of his condition" and "his predicament." My

Roman Catholicism is not a "condition" or a "predicament," no matter

what snotty American Protestants might think. I have willingly chosen

my faith, and I don't need to be patronized by any psalm-singing

Quaker. Got that, Bob?

OK--now that we've cleared the air let's

turn to some serious demolition work.

Darling must be unaware of the reception

that Tennyson got in his own day, and immediately afterward, if he

thinks that my low opinion of In Memoriam is that of "a critic

trapped in his own time." Tennyson was savaged by many nineteenth-century

commentators. Despite his popularity with the British bourgeoisie

(the perfect audience for that sentimental, wheezing, hurdy-gurdy of

a poem, In Memoriam), quite a number of Tennyson's contemporaries

shared my viewpoint of his work. Carlyle called his poetry

"the inward perfection of vacancy." Alfred Austin dismissed

it as "the poetry of the drawing room." Gerard Manley Hopkins characterized

his work as "Parnassian" in the derogatory sense. Swinburne

(a master of the skewering put-down) referred to Idylls of the

King as "Morte d'Albert, or Idylls of the Prince Consort"--a cruel

but apt reference to Tennyson's toadying complicity in Queen Victoria's

morbidly prolonged mourning for Prince Albert. But best of

all was the opinion of one reviewer of In Memoriam, who guessed

that the anonymously published poem was an emotional effusion from

the "full heart of the widow of a military man." What an appropriate

judgment, and a lot more devastating than the one I quoted from Whittaker

Chambers. So I ask Darling: Are all these people "modern critics,"

trapped in a twentieth-century viewpoint?

The main issue of contention between Darling

and myself is the question of didacticism in poetry. Darling

says "I may have a certain religious or philosophical point of view,

but that doesn't mean I'm trying to convert everyone to it.

However, I could inform people of that view without earnestly attempting

to save their souls."

Well, Good God, isn't that precisely the point

I made in my essay "The Curse of Didactic Verse," when I distinguished

between informative-didactic and manipulative-didactic poetry?

Darling's response to that first essay was to reject the distinction

out of hand. Now all of a sudden he's backpedalling on his

original dismissal of my point. It seems that Darling realizes he

has gotten onto shaky ground, and is now trying to retrace his steps.

Moreover, I never said that manipulative-didactic verse was "proselytizing"

in the literal sense. The fact that a procedure is manipulative

is exactly why it cannot overtly proselytize. It must disguise

its goals. As I said in my original essay, manipulative-didactic

poetry generally tries to cover its tracks.

In regard to liberal schoolteachers, Darling

asks "If one's learned nothing, what is there to forget?" Alas,

he missed my reference to Talleyrand, the source of that famous quotation

on the restored Bourbons. The quote alludes to that royal family's

pigheaded insistence on seeing matters in the old feudal way, despite

all the revolutionary turmoil of Napoleonic Europe. I used it as

a parallel to the attitudes of liberal schoolteachers--and believe

me, there's no one more invincibly ignorant than a unionized civil-service

liberal schoolteacher. Are there conservatives as well as liberals

who suffer from this sort of myopia? Sure. But conservatives

don't control the network of education in this country. Liberals

do. I think Darling knows that, but it's something he'd rather not

discuss. It might blow his cover as a faux conservative.

When it comes to the question of ethics in

poetry, Darling betrays that gaseous Emersonian vagueness for which

Americans are rightly ridiculed throughout the rest of the world.

Just look at the basic outline of our dispute. Darling starts by

claiming that the ethics of a poem "matter." I then retort

that different poets have very different sets of ethics, some of them

irreconcilable. I mention specific instances of excellent poems that

might be seen as unethical from certain points of view. And

all Darling can reply is "I am speaking of an ethical approach, not

the application of one's own personal guesses at the ethical."

This is exactly the sort of statement that sounds wonderfully nuanced

and measured, but which on analysis proves to be utterly meaningless.

How in logic's name can you take "an ethical approach" to anything

without following the specific set of ethics to which you are personally

committed? Darling is saying, in effect, "I am not guided by specific

ethical principles when composing a poem, nor do I consult them when

criticizing other poems, but nevertheless I approach the whole matter

ethically." This is what happens when you read too much In

Memoriam--haziness and imprecision become a kind of mental tic.

Ethics refers to a set of guidelines for behavior.

They may be negative, in the form of strictures; or positive, in

the form of exhortations; or a mix of both. But a code of

ethics is always specific. It's not some vague atmosphere

of good intentions. Here Darling's core liberalism is as apparent

as the Rock of Gibraltar. For him, ethics is "an approach."

This is the typical liberal fog--directionless feeling groping towards

an undefined hope, a "waiting for the Light." Historically,

it's Kant's categorical imperative filtered through the lens of Emerson's

idealism and Feuerbach's pipedreams, and finally issuing forth in

the saccharine placidity of Norman Vincent Peale. It would be a bore

if it weren't such a menace to rational thought.

When you have a mentality shaped by such influences,

you really can't be a good literary critic. Your commentary

is hopelessly hobbled by the vagueness of an unstated belief-system,

which you are "approaching," to use Darling's term. Everything you

say will be tentative and provisional and based on dreamy wishes

rather than ascertainable facts. In short, your scholarship will

approximate that critical mass of lethal vapidity for which In

Memoriam is the perfect symbol.

On the other hand, if you treat poems like

coal seams (which is just a metaphor for the principle of l'art

pour l'art), you are free to compose and criticize without worrying

about "ethical" concerns. You can have the strongest personal

set of ethics in the world, and it need not affect your literary work at

all, if you don't let it. You have complete aesthetic carte blanche

to produce the very best verbal creations that your talent allows.

This is called freedom, Bob--and without it poetry starves.

And no boring Emersonian vagueness or Puritanical do-goodery or "ethical

approaches" can substitute for it.

That's what poetry is--a licensed zone of

hyperreality in which one can speak and imagine anything one pleases.

This is why I can write a poem like "The Missionary's Position,"

taking a specifically non-Christian view of evangelization. Darling,

of course, can't deal with that: "Gee, if Salemi is a conservative Roman

Catholic, how come he writes a poem with ideas that conservative Catholics

reject?" Well, DUH!!! I can write whatever I please as a poet,

if I think that it's good poetry. And so can Sylvia Plath.

Does Darling realize how asinine he makes himself by criticizing

the brilliant rant-poem "Daddy" on a moral basis? He sounds

like Mrs. Grundy tut-tutting about a social faux pas as he

pompously intones that Plath's poem "clearly fails on ethical grounds."

It does? Well, Golly Gee, Bob--it's great to know that.

I'm sure Sylvia Plath would really be troubled to hear of your adverse

judgment.

"Daddy" succeeds as a poem because it works,

the same way that an engine succeeds if it turns over or an airplane

succeeds if it flies safely. This is why it is truly absurd

for Darling to assert that the most frequent target of my criticism

"seems to be the cultural relativists." I can't think of a more obtuse

reading of my literary allegiances. I welcome any kind of poetry,

on any subject and from any viewpoint, as long as it works and is

excellent. A poet's skill and ability to create new things

out of language are what I value above all else.

Here is the crux of Robert Darling's problem,

and the real explanation of why he was so angry about my attack on

didactic verse. Darling is essentially a moralist, not a literary

critic. I am open to any well-crafted poem, but Darling can't

be, because of his "ethical approaches." He has a moral hangover

from the nineteenth century. I don't. So for Darling

to suggest that I'm fighting "cultural relativists" is more than

obtuse--it's bizarre. If poetry is a licensed zone of hyperreality,

then the issue of moral relativism (which may be important in a real-world

situation) is simply irrelevant in poetry or the critique of poems.

A good illustration of what I mean is Darling's

reiterated question about a poem celebrating Nazi atrocities in World

War II. It's the height (or nadir) of absurdity for Darling

to ask me to pass judgment on a hypothetical poem before it has even

been written. Here again, we see the ingrained pietistic liberalism

of Darling's approach to literature: he seriously imagines that literary

judgment can be given on a work that does not yet exist, purely on

preconceived political and ethical grounds. Sight unseen, a

certain type of poem has to be "bad." It must be comforting

to be that clairvoyant.

Nevertheless, since Darling is so insistent

on knowing whether a good poem could be written in praise of Nazi

atrocities, I'll let him answer the question himself. Here

is Robert Darling on what can constitute poetry, from his essay "The

Loaded Terminology of the Poetry Wars," contained in the EP&M archives:

Poetry can

be good or bad, mundane or sublime,

discursive

or concentrated, wise or wrongheaded,

moral or

immoral, religious or blasphemous, or

any combination

of these or other properties. The

one quality

defining a work as poetry is that it

must be written

in verse.

It seems to me that anyone writing something

like that would have to believe that a good poem praising Nazi atrocities

is possible. Or has Darling changed his mind since the publication

of that essay? I guess that's the convenient thing about being

an "Enlightenment Puritan"--you can talk out of both sides of your

mouth on the same website.

This is what I meant when I said earlier that

Darling is trying to straddle the fence. The above quote is

as l'art pour l'art as you can get--extremely so, since it

defines poetry strictly in terms of verse structure. And yet Darling

has the cheek to attack me for "extreme privileging of form over

content," and for taking a position similar to that of the 1890s

Decadents. Who the hell does he think he's kidding? The

quote given above from Darling's essay is simon-pure aestheticism,

and could have been written by Theophile Gautier. No--Darling's

positions (like those of all fence-straddlers) are merely tactical and

designed to keep him "in the middle."

This is why Darling is so anxious to triangulate

himself between Diane Wakoski and Joseph Salemi--as if she and I

were dangerous extremists who have to be pushed aside in favor of

that broad band of open-minded, even-handed, moderate, balanced,

thoughtful types like... well, like Robert Darling. lt's a

quintessentially liberal tactic: Disavow anyone with forthright opinions,

and position yourself in the middle of the road, wrapped in a fog

of bien-pensant benevolence. This way you can stand

up to the Wakoskis and pretend that you're a big brave defender of

tradition; and stand up to the Salemis and get kudos from your colleagues

for being "enlightened." It's a pleasant little game, as long

as no one asks you the specific questions that I've asked Darling here.

Darling's silliest contention is that I'm

trying to banish "meaning and human intention" from poetry.

He knows very well that I said nothing of the sort. Disliking didacticism

doesn't imply that one hates all meaning or rational statement.

The plain fact is that if one writes in a human language, using accepted

grammar, syntax, and inherited vocabulary, meaning will be inextricably

part of one's poem. Such a traditionally composed poem can be a self-referential

work of art and still present coherent meaning to its readers. Darling

is trying--unsuccessfully--to change the terms of this debate by

confusing ethics with meaning--once again, because

he knows he's on shaky ground. If a poet says "The dawn breaks

grey over the horizon" he is presenting meaning. If he says

"We should all vote for Al Gore" he is being didactic. Got

that?

Darling complains that I left "unanswered"

his assertion that the middle class dislikes satire because they

consider it non-serious, and not because it is violent. Well,

my experience tells me otherwise. The middle classes are a

gutless bunch, and are terrified of anything shocking or extreme.

That's why they flock to malls, theme parks, and gated suburban communities.

It may be true that as a group they prefer what they call "serious"

poetry, since they are still in thrall to the Arnoldian mindset.

But I know this: satire scares the wits out of them. They are

frightened by anything that disturbs their perfect little Martha

Stewart cocoon.

While we are on this subject, let me say the

following. If Darling thinks that "middle class" is purely

an economic description, then he knows nothing about the sociology

of the United States, or even the developed world as a whole. Middle

class means an outlook, an attitude, an approach, an entire Weltanschauung,

as

the Germans say. The whole drive of bourgeois life is not primarily

towards the accumulation of money (though that is one symptom of

such a life), but the development of a certain kind of self-image.

And that image is totally different from the self-image cultivated

by, say, an old-fashioned aristocrat, or a tough ghetto street kid,

or a Hasidic Jew, or a professional soldier. It has nothing

to do with money. The British royal family is immensely rich, but

the whole brood has been totally and hopelessly middle class since

the accession of Victoria in 1837. As for there being a distinction

between bourgeois and middle class, well, that's the

kind of distinction you grasp at when you're losing an argument.

Is this the best Darling can do?

I've saved for last a brief comment on Robert

Darling's rhetorical approach. He prides himself on being a

very careful user of language, and on eschewing "propaganda" and

"loaded terminology." OK--so let's take a look at a sample

of the sort of language Darling uses when replying to my last essay: hysterical,

rigid, narrow, propagandized, raving, overkill, decibel levels, extremes,

bogeymen, black and white, all-or-nothing, simple-minded.

You would think I had delivered a harangue

at the Nuremberg rally of 1935. Let any disinterested person

read my three contributions to this debate on EP&M, and then

judge if those words are applicable to my prose.

I've been a teacher of rhetoric and a polemicist

for over thirty years. It's characteristic of liberals to use rhetoric

that paints their enemies as dangerous and noisy, and themselves

(by implication) as sweetly reasonable. You might even say it's the

only rhetorical approach they know.

Joseph S. Salemi

If menu is not visible at left, select BACK on

your browser.