EP&M Online Essay

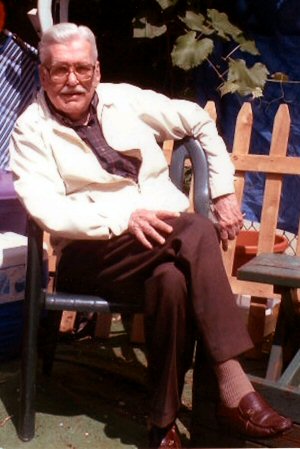

WILLIAM F. CARLSON

1921-2007

by

Joseph S. Salemi

William F. Carlson

Photograph by Gabriel Benitez, grandson

On January 29, 2007, William F. Carlson died

after a protracted battle with cancer. He was the Editor of Iambs & Trochees, and my close

friend. He leaves his wife Irene, his daughter Anne Marie, and

two grandsons, Gabriel and George.

I first met Bill Carlson over twelve years

ago, when he ran a small poetry reading series in lower

Manhattan. He had already been associated with the journal Hellas, and had published a number

of his own poems in little magazines around the country. Bill was

also a novelist, whose autobiographical No Souvenirs To Remind Me is a

gripping account of his experiences as an ambulance driver and

paramedic during the Second World War.

Bill came to poetry late in life, after taking

one of Alfred Dorn’s introductory courses on formal poetry in the

1980s. Those justly celebrated seminars brought a great many

persons to poetry who might otherwise have never considered the art’s

riches. After Bill Carlson had attended one of them, he was

hooked forever on poetry.

It was not always an easy match. Carlson

was a tough New York kid who had spent part of his childhood in an

orphanage, and who had worked long years at a dull civil-service

job. He also had seen some of the most savage fighting of the war

in Belgium and Germany during ’44 and ’45. As a member of the

ambulance corps he was unarmed, and took no part in actual

combat. But those were the days before helicopter medevac, and

Bill was right there in the midst of it, taking the same risks as any

infantryman. In his case, however, he was on a mission of mercy

to the wounded. And that mission was universal—as he said to me

once, “If a soldier was wounded I picked him up, regardless of his

uniform. What was I gonna do… leave some kid screaming because of

the color of his tunic? The blood all looked red to me.”

These chastening experiences left Bill

somewhat rough around the edges, so to speak. He was a

hard-drinking, hard-smoking, and hard-talking man. He was also a

serious professional gambler who had the steely toughness that success

in such a profession requires. His temper, when aroused, could be

volcanic. I’ll never forget his rage at my slowness and

mathematical incompetence when he tried in vain to teach me how to win

at craps and blackjack. “You can’t count, Salemi!” he screamed at

me. All I could do was mumble an apology for my ineptitude at

figuring odds.

And yet this hard-bitten man had a very gentle

and affectionate side to his nature. He was especially kind to

young poets, who he felt needed special attention and nurturing if they

were to blossom. And he loved good formal poetry with a genuine

tenderness. He was always enthusiastic about such poems, and

loved to discuss their structure, their meaning, and their aesthetic

effect. A battered and dog-eared copy of Babette Deutsch’s book

on metrical form was his constant companion, and he would read chapter

and verse from it with the same kind of apodictic certainty that one

finds in fundamentalists who quote Scriptural text. When it came

to formal poetry, Bill Carlson had the zeal of a new convert.

He founded Iambs

& Trochees because he was “fed up,” as he would growl, with

the “sameness” and “emptiness” of mainstream free verse. Bill

knew that writers could produce something better than the narcissistic

drivel and feelgood emotionalizing that have hijacked the name of

poetry today. And with the tough-minded audacity typical of him

and his generation, he decided to start a magazine “for the good

stuff,” as he put it. Bill did this despite the fact that he was

in his late seventies, and had only rudimentary computer skills in the

beginning. Obstacles never fazed him. He also knew that

there wasn’t the slightest chance of recouping the financial loss that

a print magazine entails today. “I don’t care,” he said, with an

impatient wave of his hand. “I’m gonna do it.” And do it he

did. Within three years, Iambs

& Trochees became one of the premier formalist poetry

journals in America.

I last saw him on Saturday, two days before he

died. The cancer had ravaged him terribly, and I barely

recognized the vigorous, argumentative man whom I had worked and fought

with for nearly five years. He had wasted to a wraith-like

figure. But his eyes still shone with fire, and I knew that the

inner core of Bill Carlson was still there, like hot sparks in an

ember. He could no longer speak for exhaustion and

weakness. All he could do was transfix me with an unearthly gaze,

as if he had seen beyond the limits of mortality.

He will be missed—not just by friends and

family, but by the world of poetry.

Joseph S. Salemi

NOTE: A selection of William F. Carlson’s published poetry

can be read in the e-book section of The

New Formalist web magazine, at www.formalpoetry.com. His

e-book is titled “Memorial Day—The 30th of May.” Carlson

also published a collection of his poetry with Somers Rocks Press, No Sun, No Shadow, which can be

purchased at http://www.expansivepoetryonline.com.

Joseph S. Salemi